Editor’s Note: This feature is part of CNN Style’s series Hyphenated, which explores the complex issue of identity among minorities in the United States.

Picture Captain America. Maybe you see the blue-eyed, blond-haired man from the comics, or maybe you see Chris Evans, the actor who played him in the movies.

But what if one of the most quintessential American superheroes was a bearded, brown-skinned, turban-wearing Sikh?

It’s a question Vishavjit Singh has been posing for the last decade.

In 2013, a photographer convinced the cartoonist to don a Captain America costume for a shoot on the streets of New York. Singh was reluctant at first – his thin frame didn’t fit the buff image typically associated with the superhero. Besides, he got enough nasty looks and comments because of his turban. He didn’t need to attract more attention.

The response when he put on the suit, though, was unexpected. A stranger came up and hugged him. Police officers took photos with him, and firefighters offered him a ride on their truck. He even got pulled into a wedding.

“It was like I stepped into a parallel universe,” Singh said in a Zoom interview.

Something about a Sikh Captain America seemed to resonate with people. And if wearing that uniform could make people think about the superhero differently, he thought, then maybe it could change negative perceptions of Sikhs too.

Singh has been on a mission ever since.

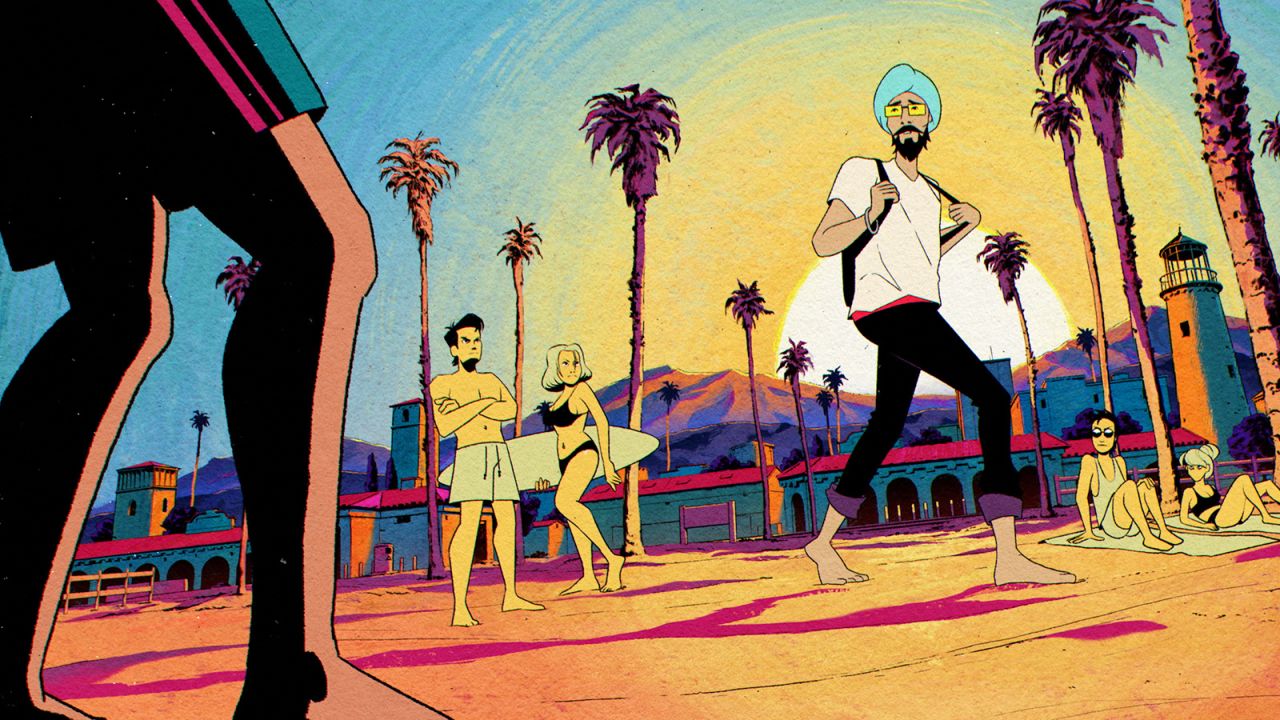

His latest effort is “American Sikh,” an animated short film he co-directed with Ryan Westra. The film, one of several animated shorts hand-selected by Whoopi Goldberg, premiered this month at the Tribeca Film Festival. Over eight minutes, “American Sikh” tells the story of how Singh came to adopt his alter ego.

Singh spent his life feeling like the other

Singh was born in the US, but largely grew up in New Delhi, India, where a series of events when he was around 13 changed how he saw himself.

In June 1984, then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi ordered Indian troops to storm the Golden Temple – the holiest Sikh shrine – in a counterinsurgency operation against Sikh militants who were calling for an independent Sikh state. At least 1,000 are estimated to have been killed in the attack, though human rights groups put the death toll much higher.

Tensions between Sikhs and the Indian government grew, and Gandhi was assassinated by two of her Sikh bodyguards on October 31 of that year. In the aftermath, angry mobs targeted thousands of Sikhs in New Delhi and other cities in India. Singh said a mob showed up to his home but his family ultimately escaped unscathed and spent the next few nights hiding out in the house of a Hindu neighbor. When they returned, he said his school and local gurdwara had been partly destroyed, while countless businesses had been burned to the ground.

Nearly 3,000 Sikhs were killed throughout India over three days, according to official estimates, and many women were raped. Years passed, and despite the scale and brutality of the violence, few perpetrators and instigators of the attacks were convicted.

As Singh says in the film, “no part of me felt Indian anymore.”

“I saw that you can do something like 1984 November and get away with it,” he added. “That had a very profound impact on my sense of who I am or how the world perceives me.”

9/11 made others see him as an enemy

Singh returned to the US in the ’90s to attend college, hoping for a fresh start in his home country. But there, he was treated like an outsider – strangers called him “genie” and “raghead,” or told him to “go back home.”

It was as if he didn’t belong anywhere.

After a while, Singh grew tired of standing out and tried to fit in. He removed his turban, cut his unshorn hair and shaved his beard – an unprecedented move in his family. Giving up these visible markers of his Sikh faith worked to an extent. People no longer stared at him on the street. As he distanced himself from Sikhism though, Singh said he felt lost.

“I had an identity crisis,” he said. “Am I American? South Asian? I knew I was not Indian, because (the anti-Sikh massacre of 1984) had cleared that off the deck. But (was I) Sikh, not Sikh?”

Over the years, Singh experimented with many different identities, as captured in a 30-second sequence in “American Sikh.” He embraced Buddhist philosophy and practiced Taoist meditations. That period of spiritual exploration eventually led him back to his Sikh faith. He started growing his hair back out. In 2000, he moved from California to the East Coast, and in August 2001, he began tying a turban again.

A month later, his turban would once again make him a target.

Singh was working just north of New York when two planes flew into the Twin Towers on September 11. Almost immediately, he felt others looking at him with suspicion. Sensing that things were about to get even more difficult for people who looked like him, Singh worked from home over the next few weeks. Meanwhile, there were reports of Sikhs – and anyone else who was perceived as being Muslim – being attacked.

If Singh was seen as an outsider before 9/11, he was seen as an enemy after the attacks. People flipped him off on the highway, and their insults took on a new tone.

“It was so ubiquitous,” Singh said. “I was reminded every day of being the other – going through airports, going out on the streets, by young and old, being called a terrorist … the worst of names, Osama bin Laden, Taliban.”

Singh turned to newspaper op-eds and editorial cartoons to process the hate and discrimination being directed at his community, and one in particular – a cartoon by Mark Fiore titled “Find the Terrorist in Your Neighborhood” – stuck with him.

“He had captured the predicament of brown people – Muslims, Hindus, Sikhs, Hispanics – who were being targeted after 9/11,” Singh said. “He had flipped the argument by saying those who are committing acts of hate against fellow Americans are actually the terrorists.”

Soon enough, Singh was drawing his own cartoons of Sikh characters.

He wants others to see Sikh Captain America as just American

In summer 2011, Singh saw a promotional poster for “Captain America: The First Avenger” that sparked an idea.

“I had this vision that Captain America is going to have a turban and beard,” he said.

Singh drew a muscular Sikh man in a Captain America suit on a large banner and took it to New York Comic Con that year. From the reception he got, he knew he was onto something – a young White boy appeared so captivated by Sikh Captain America that Singh gave away one of his only copies to him.

“I never fathomed that a 10-year-old White kid would connect to a turban and bearded Captain America,” Singh said. “If that kid could connect, maybe others could connect as well.”

The original Captain America was conceived by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby during World War II as a response to Nazi Germany, and reflected its creators’ belief in American exceptionalism. Singh’s Sikh Captain America subverted typical ideas of patriotism – instead of fighting Nazi agent Red Skull and other members of the Axis Powers, Sikh Captain America would fight hate crimes and intolerance in the US.

Later, after Singh donned the Captain America uniform for the 2013 photoshoot, Singh said he started getting invitations to appear on late night shows and to speak to children in schools. Another person who expressed interest in his story was filmmaker Westra, who had worked on a few other projects about Sikh issues. They collaborated on “Red, White and Beard,” a short documentary that was released in 2014, and in 2018, they started working on “American Sikh.”

“There’s just so little positive Sikh representation in the media, both fiction and on the news,” Westra said in a Zoom interview. “When people see Vishavjit dressed as Captain America, the reason why they get excited and why it’s a special thing is because they’ve never seen anything like that before.”

While it’s heartening to see people respond so enthusiastically to a turbaned and bearded Captain America, Singh and Westra aren’t naive about what it will take to combat bias and prejudice in the US. Westra recalled an incident that took place on the day of that photoshoot in 2013 – Singh went into a Starbucks to change out of the Captain America suit and into normal clothes, and when he stepped outside, someone shouted “Osama” at him.

“It was crazy to me that the simple act of changing the clothes on his body could have that severe of a change and reaction from people on the street,” Westra said.

As Singh sees it, his mission will be complete when people can see a Sikh in a Captain America suit and find it just as normal as anyone else wearing that superhero costume. In his Sikh cartoons, and in his films with Westra, Singh isn’t telling stories about Sikh characters who happen to live in America.

“I want to tell American stories that happen to have Sikh characters,” he said. For Singh, the distinction is critical.